Woman Power in Maya World

In Guatemala’s Laguna del Tigre National Park, the dense forest hides many treasures: endangered scarlet macaws flit among the treetops, while rare jaguars hunt on the forest floor. Only recently has the world learned about one of Laguna del Tigre’s greatest treasures, a 2,500-year-old city that once stood at the crossroads of the ancient Maya world. The archaeologists working on the site believe this city can answer many of the lingering questions about political events in the Peten region during the Classic Period of Maya history.

In Guatemala’s Laguna del Tigre National Park, the dense forest hides many treasures: endangered scarlet macaws flit among the treetops, while rare jaguars hunt on the forest floor. Only recently has the world learned about one of Laguna del Tigre’s greatest treasures, a 2,500-year-old city that once stood at the crossroads of the ancient Maya world. The archaeologists working on the site believe this city can answer many of the lingering questions about political events in the Peten region during the Classic Period of Maya history.

The ancient city of Waka’–known today as El Peru–first came to the attention of the modern world after oil prospectors stumbled upon it in the 1960s. Ten years later, Harvard researcher Ian Graham recorded the site’s monuments, and then in 2003 two veteran archaeologists, David Freidel of Southern Methodist University (SMU) in Texas and Hector Escobedo of the University of San Carlos in Guatemala, launched a full-scale excavation of the site.

According to the historical record, Waka’ was inhabited as early as 500 BC. The city reached its political peak around 400 AD and was abandoned some four centuries later. In its heyday, Waka’ was an economically and strategically important place with tens of thousands of inhabitants, four main plazas, hundreds of buildings, and impressive ceremonial centers. Researchers say the key to the city’s importance was its location between two of the most powerful Maya capitals–Calakmul to the north and Tikal to the east–and that in its history Waka’ switched its alliance back and forth between the two rivals. They suggest that the final choice of Calakmul may have led to the eventual demise of Waka’ at the hands of a Tikal king.

“We know a great deal about the ancient inhabitants of this site from their monuments,” Freidel writes in an article for SMU Research. “The more than 40 carved monuments, or stelae, at the site chronicle the activities of Waka’s rulers, including their rise to power, their conquests in war, and their deaths.” The location of Waka’ right by the San Pedro Martir River, which was navigable for 50 miles in both directions, gave it great power as a trading center. In addition to the waterway, Freidel suggests that Waka’ controlled a strategic north-south overland route that linked southern Campeche to central Peten. Freidel calls Waka’ a “crossroads of conquerors in the pre-Columbian era.”

One of the most intriguing people who inhabited Waka’ was a woman of uncommon power and status. The discovery and excavation of her tomb in 2004 by team member Jose Ambrosio Diaz drew a lot of attention to the site. “We knew that we were dealing with a royal tomb right away because you could see greenstone everywhere,” says David Lee, a PhD candidate at SMU who is investigating the Waka’ palace complex. Greenstone is archaeologists’ term for the sacred jade the ancient Maya used to signify royalty. The team found hundreds of artifacts in the tomb, which dates to sometime between 650 and 750 AD.

There were several indicators that this woman was important and powerful. Her tomb lay underneath a building on the main courtyard of the city’s main palace. Her stone bed was surrounded by 23 offering vessels and hundreds of jade pieces, beads, and shell artifacts. Among the rubble, the researchers discovered a four- by two-inch jewel called a huunal that was worn only by kings and queens of the highest status. Typically a huunal was affixed to a wooden helmet called a ko’haw that was covered in jade plaques. Carved depictions suggest that only powerful war leaders wore these helmets. On the floor of the queen’s tomb near her head, researchers found 44 square and rectangular jade plaques they believe were glued onto the wooden part of the ko’haw. The presence of this helmet in her torab has led the researchers to the conclusion that this queen held a position of power not typically afforded women of the time. “She may have been more powerful than her husband, who was actually the king of E1 Peril,” Lee concludes.

Although the presence of the helmet identifies her as a warlord, archaeologists have found no evidence of Maya women physically fighting in battles. What they have discovered are images of women as guardians of the tools of war. “The curation of the war helmet is one of the roles of royal women,” says the excavation’s bone expert, Jennifer Piehl. She explains that Maya iconography describes how royal women safeguarded these helmets and then presented them to their kings when they prepared for war. David Freidel says that to the Maya, war was more than just a physical act; it was also an encounter between supernaturally charged beings. Women had an active role in battle by conjuring up war gods and instilling sacred magical power in battle gear.

Other symbols of royalty were the stingray spines found in the pelvic regions of the queen’s remains. Stingray spines are bloodletting implements that were used in ceremonies by Maya kings to drain blood from their genitalia. “The association between gender and power becomes blended because this person represents both kinds of power,” explains Lee. “As we learn more, we are discovering that what our culture considers traditional ideas of male-female roles don’t hold true for Maya royalty.”

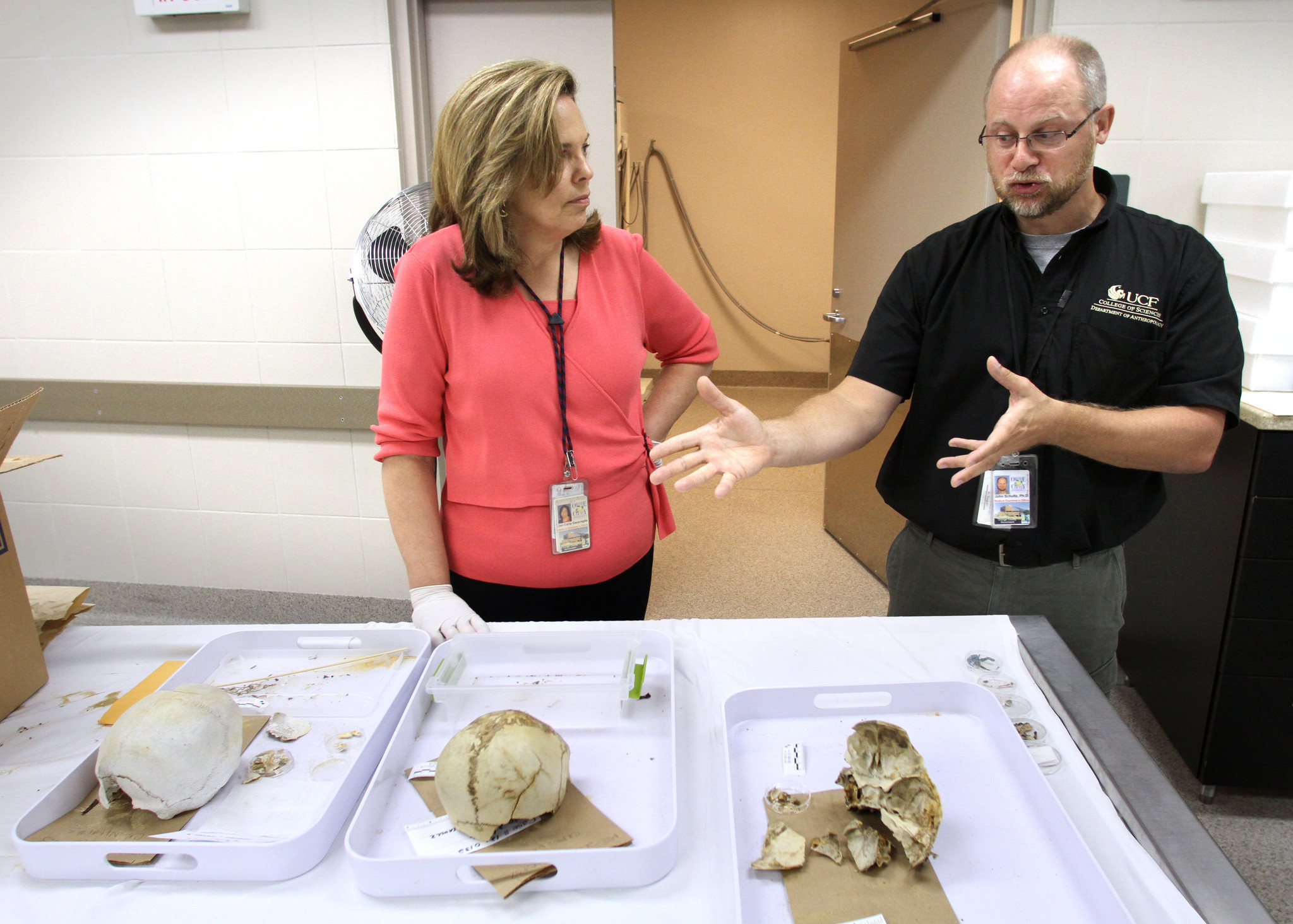

Researchers could also determine the importance of the woman by what was missing from her tomb. Some time after her burial, the tomb was opened up to remove her skull and femurs. “The cranium and crossed femurs is a very salient symbol in Maya ritual. It is the ancestor,” says Piehl. The Maya would take the skull and femurs from an important ancestor and preserve them in brandies. Maya images show how these bundles were used during ceremonies or were worn on the back of the ruler’s regalia. “They are literally carrying their ancestor around with them,” says Lee. Researchers surmise that pos session of a bundle gave legitimacy and power to the owners.

Once her status as a queen was confirmed, the question became, which queen was she? A good candidate is a woman named Lady K’abel who lived during the Late Classic period and was the daughter of the King Yuknoom Yich’aak K’ak’ of Calakmul. Researchers interpret her marriage to King K’inich B’ahlam II of Waka’ as a savvy political move for Calakamul, because a royal marriage could forge a permanent political bond between the two cities. Unfortunately the union would not prove to be a good political move for Waka’. Researchers suggest that it was considered an act of betrayal by Tikal, which eventually defeated Waka’ in 743 AD.

A detailed portrait of Lady K’abel comes from a stela dated to 692 AD that was looted from Waka’ in the late 1960s. According to Maya expert and project epigrapher Stanley Guenter, inscriptions on the front face of the stela–curated by the Cleveland Museum of Art in Ohio–clearly identify the woman as Ix Kaloomte’ (lady warlord) or Lady K’abel, princess of Calakmul. “Mosaic mask pectorals formed of greenstone, shell teeth and eye whites, and obsidian pupils found in the interment are consistent with the image of Lady K’abel on Stela 34,” Lee and Piehl posit in a recent paper. “These attributes clearly demonstrate the royal status of the woman and an identification with Lady K’abel.” Radiocarbon dating of the queen’s remains will confirm whether the woman in the tomb lived during the same time period as Lady K’abel.

Another tomb, discovered by archaeologists Michelle Rich and Jennifer Piehl in 2005, tells the story of two women from an earlier part of Waka’s history, dating back to between 350 and 400 AD. The tomb contains the remains of two women between 25 and 35 years old, placed back to back, one on top of the other, with stingray spines near their groins. The bottom woman, who was pregnant, lay face down and the top woman face up. Although the tomb is tiny by royal standards–some 3 feet wide, 4 feet high and 6.5 feet long–Rich and Piehl believe that these women were high-ranking members of a royal family.

By analyzing theft” skeletal remains, archaeologist and osteoglogist Jennifer Piehl can tell a great deal about the status of these women in life. “What we can say of the bones of the two Waka’ women is they were in excellent health–better than the majority of the Waka’ population which fits with them being royal,” she says. In addition, the lack of dental cavities suggests that unlike ordinary Maya, these women were treated to special foods, including meat, fish, and fruit.

Further evidence of the elite status of these women comes from the seven ceramic vessels that accompanied them in death. “The first thing we saw was the cluster at [their] feet of three gorgeous, museum-quality polychrome vessels,” Piehl recalls. The quality of the vessels and the symbols of royalty on them indicate that the women came from a royal bloodline. Vessels of the exact same style were also found at Tikal in a similar set of tombs containing members of a royal dynasty who were probably killed by the great fourth-century conqueror Siyaj K’ak’ from Teotihuacan. According to the stone stelae from the main plazas of Waka’, Siyaj K’ak’ also visited that city in 378 AD on his way to conquer Tikal. “My conclusion is that these are members of the royal family that was in power before the arrival of Siyaj K’ak’,” Piehl says. Freidel calls Siyaj K’ak’s visit to Waka’ the city’s “first great experience as a crossroads of conquerors.”

Rich suggests that the women were sacrificed as part of a lineage replacement, whereby one invading ruler comes in and kills the current royal family to establish his family as the only royal blood in the kingdom. “The king would have been the primary focus of sacrifice, but then the rest of the family would have to be exterminated in order to wipe out the entire ruling line,” Rich says. To prove that hypothesis, the team is searching for a king from the same time period. In 2006, Hector Escobedo and Juan Carlos Melendez uncovered the tomb of a king under the site’s main pyramid, but more research needs to be done to fully understand who that man was. Also in 2006, Rich and Varinia Matute found another ruler, but he dates to approximately 550-650, a couple of hundred years later than the women. “At tiffs point we have two rulers and no connection to the sacrificed women,” Rich says. “El Peru is a huge site, and there is so much we can learn.”

Although the archaeologists involved with this project agree that further excavations of Waka’ have the potential to fill in some of the gaps in the political history of the region, the future of the Waka’ Archaeological Project is uncertain. Laguna del Tigre, where the Waka’ archaeological site is located, is the largest nature reserve in Central America, covering some 118,600 acres of such biologically significant habitat that in 1990 it was the first site ha Guatemala named to the List of Wetlands of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. Despite its protected status, the forest of Laguna del Tigre is in danger due to illegal logging, slash-and-burn agriculture, and drug smuggling. Just as the forest is in peril, so is the city of Waka’ and any other archaeological treasures hidden in the forest.

To ensure the protection of Waka’ and the rainforest that surrounds it, Freidel developed partnerships with the government of Guatemala, the Wildlife Conservation Society, and the nongovernmental organization ProPeten to try and safeguard 230,000 acres of the forest. The group formed the K’ante’el Alliance, which means “precious forest” in Maya and refers to the mystical place where the Maya Maize God was said to be reborn and where the Maya believe their civilization began. The K’ante’el Alliance plans to protect the park by developing environmentally friendly sources of income for local communities that will celebrate the forest’s resources instead of destroy them. The hope is that Waka’ and Laguna del Tigre will continue to share their hidden treasures for years to come.

Chris Hardman contributes regularly to Americas on archaeology, science, and conservation news.

COPYRIGHT 2008 Organization of American States

COPYRIGHT 2008 Gale, Cengage Learning