Ocala- A Mayan Province in Florida

In 1539 the Hernando de Soto expedition heard fabulous stories about a province in Florida called Ocalé (pronounced Ocala, the namesake of modern-day Ocala, Florida.) It was the first location where he received reports of gold. Its inhabitants were named Uqueten and Potano. In 1564 the French settlement of Fort Caroline learned a tribe called Potonou was mining gold in the Appalachian Mountains and shipping it through Florida. Evidence suggests the province of Ocala was inhabited by various Chontal Maya tribes including the Poton and Yokot’an who were engaged in shipping natural resources back to Mexico including gold and silver.

Spanish Eyewitness Accounts

When the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto first landed in Tampa Bay, Florida in 1539 he immediately asked the local natives where he could find gold. The natives were unanimous in their replies– a province called Ocalé (pronounced Ocala.) In a letter De Soto wrote to the King of Spain, he noted:

When the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto first landed in Tampa Bay, Florida in 1539 he immediately asked the local natives where he could find gold. The natives were unanimous in their replies– a province called Ocalé (pronounced Ocala.) In a letter De Soto wrote to the King of Spain, he noted:

“there is another town, called Ocalé. It is so large, and they so extol it, that I dare not repeat all that is said….They say there are many trades among that people, and much intercourse, an abundance of gold and silver, and many pearls.”

In this letter, De Soto referred to Ocale´ as a town but elsewhere he also referred to it as a province. He also recorded a small town named Etocale´. This suggests there was both a province and two towns within it all named Ocale´. In the written accounts of the Spanish expedition compiled in the book, The De Soto Chronicles, the first town recorded in the province of Ocale´ was named Uqueten:

“These people and their Governor arrived at the first town of Ocalé, which was called Uqueten…”

Another passage stated the next town after the town of Ocale´ was called Potano:

“On the eleventh of August of the same year, the Governor departed from Ocalé….The next day they went to Potano…” (p. 262)

Thus the province of Ocala contained two towns: Uqueten and Potano.

There was also a Maya people in Mexico called the Poton/Putun. The Poton/Putun Maya were the seafarers of Mexico. According to the book Maya History and Religion, they controlled all the coastal trade routes of Central America and provided trade goods to many civilizations including the Maya:

“There was regular sea trade, controlled by the Putun, which circled the peninsula of Yucatan from the delta lands and the Lagune de Terminos to the Sula Plain of Honduras, with numerous ports of call en route. The Putun were the Phoenicians of the New World.” (p.7)

If anyone could make it to Florida certainly the Putun/Poton Maya were it. The book goes on to explain how the Spanish spelled their name both Putun and Poton and that they were in possession of gold:

“Perhaps the chief Putun town was Potonchan (note poton [u-o interchange as in Toltec-Tultec, Olmec-Ulmec, Tochtlan-Tuxtla, and the like]…at the mouth of the Grijalva [River]…almost opposite Frontera…It was at Frontera that Cortes won a hard-fought battle, small quantities of gold, and his Indian mistress-interpreter Marina, whose knowledge of Putun and, through that, related lowland Maya tongues, as well as Nahuatl, was of stupendous value to Cortes.” (p.7)

The Poton were referred to as “Mexicanized Maya” by researchers because of their mashup of cultural traits. According to the book Maya History and Religion they lived in a province called Acala (sometimes Mexicanized to Acalan):

“…the Putun established themselves… naming their land Acala or Acalan, ‘Land of the Canoe People,’…” (p.4)

This book also notes that their neighbors were the Yokot’an who spoke a related dialect of Poton. (p.10)

Thus in both Mexico and Florida, there was a province named Acala/Ocala with people named Poton/Potano and Yokot’an/Uqueten living there and who traded in gold. Within the Florida province of Ocala, De Soto recorded two towns also named Ocala: Ocale´and Etocale´. Etocale´was described as a small town. Ocale´was described as the main town and said to be very large. This naming convention is identical to the Poton in Mexico. As researchers noted in the book, The Maya Chontal Indians of Acalan-Tixchel:

“Cortes describes the settlement, which he calls ‘Izancanac,’ as a large place with many temples. Bernal Diaz refers to it as Gueyacala, ‘great Acalan,’ to distinguish it from another town known as ‘small Acalan,’…”(p.52)

Is there any more evidence among the eyewitness accounts of the Spanish that the Potono and Uqueten living in the Ocale´province in Florida were related to the Poton and Yokot’an Maya from the Acala province in Mexico? In fact, there is. In a letter De Soto wrote to the King of Spain, he noted in regards to Florida’s Ocale´:

There is to be found in it a great plenty of all the things mentioned; and fowls, a multitude of turkeys, kept in pens, and herds of tame deer that are tended….

The Maya were known for raising turkeys and herds of deer so much so that early explorers noted, “This province is called in the language of the Indians Ulumil cuz yetel ceh, meaning ‘the land of the turkey and the deer.'”

In their paper, “Earliest Mexican Turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) in the Maya Region,” researchers noted evidence for captive-raised turkeys among the Maya at the El Mirador site:

“Late Preclassic (300 BC–AD 100) turkey remains identified at the archaeological site of El Mirador (Petén, Guatemala) represent the earliest evidence of the Mexican turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) in the ancient Maya world….As the earliest evidence of M. gallopavo found outside its natural geographic range, the El Mirador turkeys also represent the earliest indirect evidence for Mesoamerican turkey rearing or domestication. The presence of male, female and sub-adult turkeys, and reduced flight morphology further suggests that the El Mirador turkeys were raised in captivity.”

In their paper, “Animal use at the Postclassic Maya center of Mayapan,” researchers noted similar farming of deer at Mayapan:

“…evidence suggests that white- tailed deer were either raised in captivity or were carefully managed in habitats surrounding the city.”

The Maya were the only known people in Mexico to raise deer and no tribes in the Southeastern U.S. were known to do this. The researchers further noted:

“The primary animals consumed at Mayapan … were white-tailed deer (23% of identified bone fragments), dog (4.4%), turkey (12.9%), and iguana (10.2%).”

As just noted, dog was another important part of elite diets at Mayapan. In the written accounts of the Spanish expedition compiled in the book, The De Soto Chronicles, De Soto also mentioned that towns in the province of Ocala raised dogs for meat:

As just noted, dog was another important part of elite diets at Mayapan. In the written accounts of the Spanish expedition compiled in the book, The De Soto Chronicles, De Soto also mentioned that towns in the province of Ocala raised dogs for meat:

“We arrived at this town, which was called Etocalé. It was a small town; we found some corn and beans and little dogs to eat…”(p.226)

He later mentioned that the dogs were mute and could not bark:

“…the Indians came forth in peace and gave them corn, although little, and many hens roasted on barbacoa, and a few little dogs, which are good food. These are little dogs that do not bark, and they rear them in the houses in order to eat them.” (pp. 280-281)

The only mute dog in the Americas was the techichi of Mexico. It was, indeed, fattened up and raised for food by several Mesoamerican groups including the Maya. In the paper, “Hot dogs: Comestible Canids in Preclassic Maya Culture,” researchers noted:

“In the Maya area at the time of the Spanish conquest a breed called techichi was noted as being Indis edulis, ‘eaten by the Indians,’ by Francisco Hernandez…and adds ‘that the Indians of Cozumel Island [off the coast of Yucatan in the northern part of the Maya area] ate these dogs as the Spaniards do rabbits. Those intended for this purpose were castrated in order to fatten them.” (p.820)

The techichi was frequently represented on dog pots in the Maya area. A people known as the Colima from West Mexico who had known contacts with the Maya are particularly famous for such pots. Numerous dog pots featuring this dog have been unearthed in Mexico. Similar dog pots have been unearthed in Georgia except they appear to represent the Chihuahua breed, not the techichi. Researchers have noted in the paper, “Genetic distance between three breeds of dogs based on selected microsatellite sequences” that Chihuahuas likely descended from techichis:

“The origin of Chihuahua is not clear, either. Probably, its direct ancestor was a dwarf dog, Techichi, bred by the Toltec people that had lived on the territory of present Mexico.” (p.96)

Thus we have both eyewitness accounts and archaeological evidence of two Mexican breeds of dogs being in Florida and Georgia. Like the Maya, the people of the Ocala province in Florida raised techichi dogs for food.

Not only were there turkeys, deer, and small dogs being raised for food but the province of Ocala was said to have an “abundance” of corn, enough to feed De Soto’s large expedition for three months:

“These people and their Governor arrived at the first town of Ocalé, which was called Uqueten, where they captured two Indians; and then he provided that some on horseback and the mules that they had carried from Cuba should go with corn to all those who were coming behind, since there they had found abundance…Having joined the army, they went to Ocalé, a town in a good region of corn…” (pp.260-261)

“He reached Calé and found the town without people…There came two horsemen whom the governor had sent, who told them that there was maize in abundance in Calé; at which all were rejoiced. As soon as they reached Calé, the governor ordered all the maize which was ripe in the fields to be taken, which was enough for three months.” (p.65)

Corn is a crop that originated in Mexico.

Thus, the Poton in both Florida and Mexico ate the same foods, raised the same animals and cultivated the same crops. De Soto noted there were many trades among Florida’s Potano and much intercourse or trading. De Soto also mentioned there were “broad roads” leading to their villages. All of these characteristics are consistent with the Poton Maya of Mexico.

De Soto never found the main town of Ocala. The native guides likely realized there would be dire consequences for themselves if they brought this band of thieving and murderous conquistadors into such a rich town. They simply told De Soto of other rich lands to the north and he hurriedly went on his way. The Poton Maya in Mexico used the precise same strategy when the Spanish arrived in their lands in Mexico, as recorded in the book, The Maya Chontal Indians of Acalan-Tixchel:

“At Teutiercas…the cacique…had ordered that the Spaniards should be led astray and diverted from the major Acalan settlements.” (p.108)

French Eyewitness Accounts

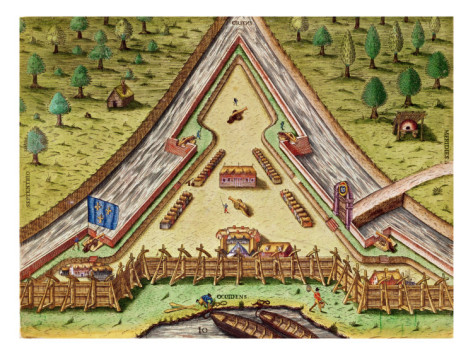

Nearly thirty years later in 1564, the French would build a settlement called Fort Caroline on the St. John’s River in modern-day Jacksonville, Florida which is northeast of Ocala. There they learned of a tribe called the Potanou (misprinted as Potavou in some printed editions of the written accounts according to the Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico). The Potanou, along with two other tribes, controlled the gold deposits in Georgia’s Appalachian Mountains.

Nearly thirty years later in 1564, the French would build a settlement called Fort Caroline on the St. John’s River in modern-day Jacksonville, Florida which is northeast of Ocala. There they learned of a tribe called the Potanou (misprinted as Potavou in some printed editions of the written accounts according to the Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico). The Potanou, along with two other tribes, controlled the gold deposits in Georgia’s Appalachian Mountains.

As related by the French artist who accompanied the expedition in his account, The Narrative of Le Moyne:

“M. de Laudonniere had been sending out men to explore the remoter parts of the country, more particularly those in the vicinity of the great King Outina, the enemy of our own neighbor, and from whom, by the channel of some of our Frenchmen who had got into relations with him, a good deal of gold and silver had been sent to the fort…Upon this, M. de Laudonniere at once sent out a person…who returned to the fort reporting that he had certain information that all the gold and silver which had been sent to it came from the Apalatcy Mountains, and that the Indians from whom he obtained it knew of no other place to get it, since they had got all they had had so far in warring with three chiefs, named Potanou, Onatheaqua, and Oustaca, who had been preventing the great chief Outina from taking possession of these mountains. Moreover, La Roche Ferriere brought with him a piece of rock mined in those mountains, containing a sufficidently good display of gold and brass.” (pp.6-7)

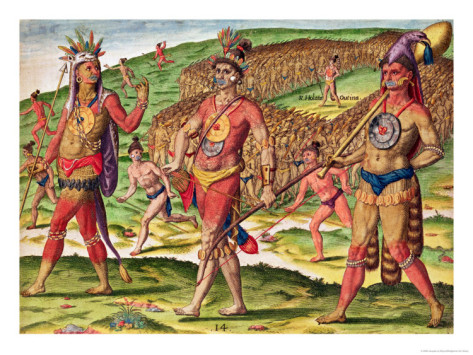

The French were amazed at the wealth of the Potanou:

“He was astonished at their civilization and opulence, and sent to M. de Laudonniere at the fort many gifts which they bestowed upon him. Among these were circular plates of gold and silver as large as a moderate-sized platter, such as they are accustomed to wear to protect the back and breast in war; much gold alloyed with brass, and silver not thoroughly smelted. He sent also some quivers covered with very choice skins, with golden heads to all the arrows; and many pieces of a stuff made of feathers, and most skillfully ornamented with rushes of different colors; also green and blue stones, which some thought to be emeralds and sapphires, in the form of wedges, and which they used instead of axes, for cutting wood. M. de Laudonniere sent in return such commodities as he had, such as some thick rough cloths, a few axes and saws, and other cheap Parisian goods, with which they were perfectly satisfied.” (p8)

The circular plates of gold sound similar to the golden disc artifacts unearthed in the sacred cenote at the Mayan site of Chichen Itza in the Yucatan by various archaeologists dating back to 1906.

Le Moyne then goes to explain how this gold was shipped from the Georgia mountains to the St. John’s River in Florida, the modern name of the Frenchmen’s River of May:

“A great way from the place where our fort was built, are great mountains, called in the Indian language Apalatcy; in which, as the map shows, arise three great rivers, in the sands of which are found much gold, silver, and brass, mixed together. Accordingly, the natives dig ditches in these streams, into which the sand brought down by the current falls by gravity. Then they collect it out, and carry it away to a place by itself, and after a time collect again what continues to fall in. They then convey it in canoes down the great river which we named the River of May, and which empties into the sea.” (p.15)

The southernmost deposits of gold in Georgia are in four rivers: Walnut Creek, Hard Labor Creek, Beaverdam Creek, and Apalachee River. All of these rivers/creeks eventually flow into the Altamaha River which flows into the Atlantic Ocean at Darien, Georgia. (See map below.)

Why would the Potanou of Georgia ship their gold to the east coast of Georgia, down the coast to north Florida, and then down the St. Johns River at Jacksonville, Florida? The St. Johns River happens to be the best short cut from the east coast of Florida to the west coast and Gulf of Mexico. This saves paddlers from having to traverse the entire peninsula of Florida. The river flows towards west Florida until it reaches the Ocklawaha River above Lake George. It then begins to turn back to the east and flows towards Titusville and Cape Canaveral.

The Spanish in the 1560s noted a tribe named the Mayaca lived at the southern end of Lake George. A shipwrecked Spaniard named Fontenada also mentioned this tribe in his accounts along with another named the Mayajuaca at Cape Canaveral and Mayaimi at Lake Okeechobee.

Above Lake George the Oklawaha River branches off the St. Johns and flows further west towards the Gulf of Mexico but without reaching it. The westernmost point is at Silver Springs in Ocala, Florida. It is in the Ocklawaha River Valley where the province of Ocala was most likely located. It appears the Potanou of Georgia were shipping their gold to the Potano of Ocala province in Florida although based on De Soto’s accounts it appears the gold was held at the main town of Ocala (which he nor archaeologists have never found) and not at Potano (where he encamped and made no mention of gold.) Archaeologists noted in the book, 1539, that they believe they have actually found the site of Potano near Orange Lake which is off of a tributary of the Ocklawaha River.

From Silver Springs, the gold would have to travel overland 24 miles before reaching another river system at Rainbow Springs. From here it could travel to the Gulf of Mexico via the Withlacoochee River.

Coincidentally, this is the exact route where the State of Florida attempted to build the Cross Florida Barge Canal in order to enable water traffic to go from the Gulf Coast to the Atlantic Coast. It appears the Poton Maya, master traders themselves, recognized this route centuries earlier.

Once here the Poton traders would travel around the Gulf of Mexico back to Mexico. This would explain why so few artifacts of gold have been found in the Southeastern United States. This gold was for an export market.

To the west of the province of Ocala are the archaeological sites of Crystal River and Robert’s Island. The Crystal River site features flat-topped pyramids, constructed of shell and limestone rocks, with a central plaza, the first such architecture and town plan in Florida. It also features pottery with Mayan glyphs and religious symbols. Silver and copper ear ornaments called ear spools were also unearthed here dating back to the first century AD. Clearly this mining operation had been going on for a very long time.

Archaeologists in their paper, “Evidence for stepped pyramids of shell in the Woodland period,” noted that the Robert’s Island complex, just a half mile down river and visible from the Crystal River site, featured stepped pyramids of shell similar to those at the Poton Maya port of Isla de los Cerros in Tabasco, Mexico.

“Perhaps the closest parallels for the stepped- pyramids of shell at Roberts Island may be found in prehispanic sites of the Yucatan. Ensor (2003) noted the presence of a number of multi-level shell mounds at the Isla de los Cerros complex, located in the Mexican state of Tabasco and dating to the Late Classic-Epiclassic/Early Postclassic period. These mounds were around the same size as the mounds at Roberts Island; some were larger at the base, but none were as tall as Mound A at Roberts Island.” (p. 359)

Isla de los Cerros was the main port for the Mayan city of Comacalco. The great Mayan city of Palenque likely traded through here as well because eventually, they conquered Comacalco most likely to control access to this port and its foreign goods.

Thus the Poton and their ancestors, the Olmec, appear to have been savvy, ambitious, master traders.

Conclusion

Multiple lines of evidence support the theory that the Ocala province encountered by De Soto in 1539 was a Mayan province. The name of the province and the two villages, Uqueten and Potano, are identical to the province of Acala in Mexico where the Poton and Yokot’an Maya lived. The people of Ocala grew corn and raised turkeys, deer, and techichi dogs for food just as their Mayan counterparts did in Mexico. They engaged in long-range trade in high-value commodities just as their counterparts in Mexico. The fact that the Crystal River site is due west of this province suggests this Mayan influence goes back centuries to at least 1 AD. The fact a tribe called the Mayaca lived due east of this province on Lake George is further evidence of this connection.