Origin of Ancient Jade Tool Baffles Scientists

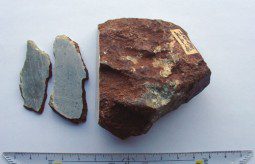

- A composite photograph of the front and back of the jade gouge shown with a centimeter scale. CREDIT: Les O’Neil, University of Otago

An international team of archaeologists and geologists has found an extremely unusual example of jade in the Southwest Pacific, thousands of miles away from the nearest known geological source. The small green artifact is about 3,300 years old and has a chemical composition that is unlike any other described jade. Found during an archaeological excavation on a coral island in Papua New Guinea, the rock is thought to have been used as a wood gouge by the people living there.

But where did it come from? The researchers, from the American Museum of Natural History, the University of Otago (New Zealand), and the University of Papua New Guinea, address this question in an upcoming special issue of the European Journal of Mineralogy on jadeitite, the rock that defines one type of jade.

- A photo of a rock sample collected by C.E.A. Wichmann in 1898 from the Torare River in the Papua province of Indonesia. On loan from Utrecht University, the rock is thought to be a match to the Emirau Island jade artifact. (R.L.M. Vissers, Utrecht University)

Jade is a general term for two extremely tough rocks—jadeite jade (jadeitite) and nephrite jade, each composed almost entirely from a single mineral. Throughout history, these rocks have been made into tools and ornamental gems that were worn, traded, and treasured. Many nephrite jade sources exist, but the prominent locations are China, New Zealand, Russia, and Canada. Far rarer is jadeite jade, which was used by people living in what is now Central America and Mexico over a span of two millennia prior to the arrival of European colonists. “In the Pacific, jadeite jade as ancient as this artifact is only known from Japan and its usage in Korea,” said George Harlow, a curator in the Museum’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences and the lead guest editor for the special journal issue. “It’s never been described in the archaeological record of New Guinea.”

The artifact was recovered from Emirau Island in the Bismark Archipelago. It was likely dropped from a stilt house into the water below and covered by years of beach sand.

After preliminary analysis at Academia Sinica (Taiwan) and the University of Otago, the gouge was sent to the Museum, where it was studied with x-ray microdiffraction, a technique that bounces a small beam of x-rays off the specimen to elucidate the atomic structure of the material, and, consequently, the types of minerals it contains. Harlow also used the Museum’s electron microprobe to determine the chemical composition of the minerals in the jadeitite.

“When we first looked at this artifact, it was very clear that it didn’t match much of anything that anyone knew about jadeite jade,” Harlow said.

The chemical composition of the jadeite in the rock is substantially different from that of other jadeitite samples. Jadeite, a mineral of sodium, aluminum, silicon and oxygen in its pure form, is usually mixed compositionally with small amounts of calcium, magnesium, and iron, representative of the minerals diopside and, to a lesser extent, hedenbergite. The jadeite in the newly discovered jade, however, has almost no diopside content and, instead, contains iron without added calcium, representing the mineral aegirine, containing sodium, iron, silicon, and oxygen.

In addition and equally unusual, the artifact contains minerals rich in niobium and yttrium, which, according to Harlow, have never been previously observed in a jadeitite. “It makes very little sense based on how we know these rocks form, and certainly not in the concentration that we see,” he says.

But the even bigger mystery is where this unusual rock came from. Only one jadeite source has been reported with similar chemical properties—a site in Baja California Sur, Mexico. If this were the gouge’s original home, though, it would have had to been transported across the Pacific, a highly improbable scenario for the Neolithic people of the time.

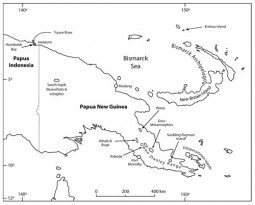

- Map of the area around eastern New Guinea showing the location of Emirau Island, where the jade artifact was found, and Torare River, the possible source of the rock.

“This jadeite tool points toward prehistoric contacts with the north coast of New Guinea,” said Glenn Summerhayes, an archaeologist at the University of Otago and a co-author on the paper. “The users of this jadeite gouge were part of the movement of Austronesian-speaking people we call Lapita, who appeared in the western Pacific almost instantaneously around 3,300 years ago, then quickly spread across the Pacific out to Samoa in a couple hundred years, and from there formed the ancestral population of the people we know as Polynesians. Where they came from beforehand has always been a matter of debate, so any find linking these early Lapita settlements with the west is important in modeling the nature of their beginning.”

After investigating the possibility of other sources in Asia and coming up empty-handed, the researchers came across a clue in the form of an unpublished manuscript by German scientist C. E. A. Wichmann. A professor at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, Wichmann collected some curious rocks from the Torare River in the Papua province of Indonesia in the beginning of the 20th century. According to Wichmann’s manuscript, the rocks he collected have chemical properties that are very similar to the Emirau Island jadeite.

Harlow is now investigating samples from Wichmann’s collection, on loan from the Institute of Earth Sciences at Utrecht University and the National Museum of Natural History in Leiden, to determine if a new source for this unusual type of jadeite has been found. So far, the data support the hypothesis.

“The discovery of this artifact’s source can be eagerly anticipated as something geochemically extraordinary,” Harlow said. Other authors on the paper include Hugh L. Davies, University of Papua New Guinea, who brought the Wichmann work to light, and Lisa Matisoo-Smith, University of Otago.

American Museum of Natural History (amnh.org)

The American Museum of Natural History, founded in 1869, is one of the world’s preeminent scientific, educational, and cultural institutions. The Museum encompasses 45 permanent exhibition halls and galleries for temporary exhibitions, the Rose Center for Earth and Space with the Hayden Planetarium, state-of-the-art research laboratories and five active research divisions that support more than 200 scientists in addition to one of the largest natural history libraries in the Western Hemisphere and a permanent collection of more than 32 million specimens and cultural artifacts. Through its Richard Gilder Graduate School, it is the first American museum to grant the Ph.D. degree. In 2012, the Museum will begin offering a pilot Master of Arts in Teaching with a specialization in earth science. Approximately 5 million visitors from around the world came to the Museum last year, and its exhibitions and Space Shows can be seen in venues on five continents. The Museum’s website and growing collection of apps for mobile devices extend its collections, exhibitions, and educational programs to millions more beyond its walls. Visit amnh.org for more information.

Follow Become a fan of the Museum on Facebook at facebook.com/naturalhistory, or visit twitter.com/AMNH to follow us on Twitter.