Mayan Glyphs, Figurines at Mandeville Site in Georgia

The Mandeville site in Georgia is the earliest site in the state to feature a flat-topped earthen pyramid mound and may be the earliest in the entire Southeastern U.S. A large plaza was located in front of the earthen pyramid making this also the first instance of a pyramid-plaza site plan found in Georgia (if not the entire Southeastern U.S.)

Archaeologists who first studied the site such as Edward McMichael and Arthur Kelley, noted in addition to its Mesoamerican architecture and site plan, the Mandeville site also featured clay figurines similar to those produced in Mexico. They argued the site was built by or strongly influenced by people from Mexico.

To the above evidence, I offer that Mayan figurines are, indeed, found at the site and Mayan glyphs are found on the pottery.

Mayan Figurines

A figurine was unearthed at the Mandeville site of a person wearing a unique head covering.

The black and white photo (left) of this figurine published in the dissertation, A Re-analysis of the Mandeville Site, shows a circular design on the upper right side of the headdress. The figurine is currently housed in the Columbus Museum of Arts & Sciences in Columbus, Georgia. Color photographs shot from two angles reveal the same circular design clearly in the top view (right) as a bulge in the headdress at the same location. This design feature suggests something was attached to the headdress. The top view also reveals the folds in the headdress.

The figurine appears to be a crude version of a more exquisite Mayan artifact unearthed at the Jaina Island site in Mexico:

The Mayan figurine shows a headdress with similar folds as the Mandeville version. Interestingly, the Mayan figurine also shows a circular design attached to the right side of its headdress. One researcher in the paper, “Mushrooms Encoded in Pre-Columbian Art,” suggested the design represented the Amanita muscaria hallucinogenic mushroom.

Instead of the Mandeville figurine being a crude copy of the Mayan figurine, it could simply be a representation of the same individual (or class of individual, i.e., trader/shaman) created by a local Mandeville artisan with less skill than her Mayan counterpart.

Perhaps the person represented in both figurines was a type of trader (drug dealer?) who advertised his goods via this specific headdress. The drum he’s holding in the Mayan version could be the way he announced his presence when entering a new village. Or he could be a shaman or other religious person who used drumming and hallucinogens as part of a religious ceremony.

The researcher noted in her dissertation that one more similar figurine was known from Florida.

Mayan Glyphs

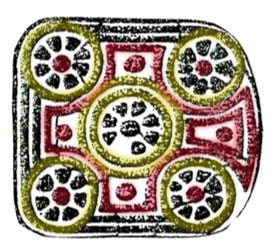

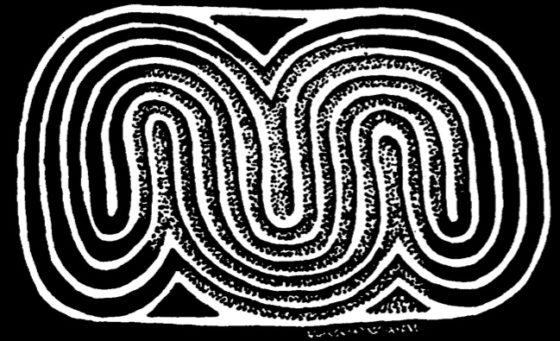

Some of the earliest Swift Creek pottery was also unearthed at the Mandeville site. This pottery featured complicated designs that were first carved into wooden paddles then stamped into the wet clay of the pot and then fired. These designs have been noted for their Mesoamerican designs and Mayan glyph motifs.

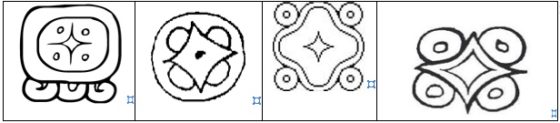

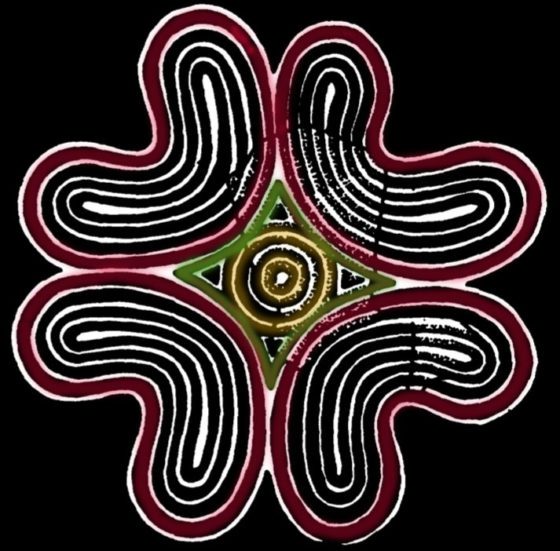

One such Swift Creek design unearthed at the Mandeville site featured a central diamond shape surrounded by four circles.

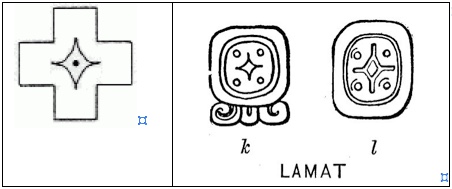

This design is similar to the Mayan Lamat glyph which is a symbol for Venus. Below are several different versions of this glyph found throughout the Maya region.

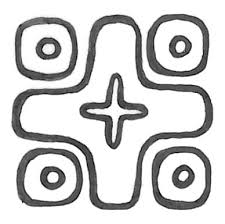

Another design from the Mandeville site featured a cross figure surrounded by circular designs:

This design is also similar to another version of the Mayan Lamat glyph which is a symbol for Venus.

The Mandeville glyph also contains another design feature associated with Venus: the quincunx. The quincunx is a pattern of five dots with four dots forming a square with a fifth dot in the middle. Among the Maya, this design was closely associated with Venus.

The Mayan Lamat glyph had three basic variations. One featured a diamond-shaped design surrounded by circles like mentioned previously. Another featured a cross-shaped design surrounded by circles such as the one above. The final version combined both the cross and diamond-shaped figures sometimes with the surrounding circles and sometimes without.

The Mandeville site also had two versions of this third cross-and-diamond type.

As stated previously, the Mayan Lamat glyph is a symbol for Venus. Although we do not know the meaning of these Swift Creek designs, we can assume they also have a stellar interpretation since they featured a circled-dot or circumpunct in their design. The circled-dot or circumpunct design was a known star symbol among Georgia’s Native Americans. It was also a star sign in Mesoamerica. For instance, there were five circumpuncts in the headband of the god Tlaloc who has Venus associations. The number 5 has long associations with Venus throughout Mesoamerican such as with the quincunx glyph. The previous Mandeville glyph featured five circumpuncts in a quincunx design with the center circumpunct taking on a four-pointed-star design.

Interestingly, both Mandeville glyphs were cleverly designed with four crescent shapes to form the cross shape. The second glyph included the circumpunct star symbol inside the crescent suggesting a ‘star-in-crescent’ design (most familiar as an Islamic symbol but actually predates Islam.) The star in ‘star-in-crescent’ symbols nearly always represents Venus since this is the most common “star” to appear near the moon in this configuration. It does so on a nearly monthly schedule.

The Maya also had a version of this ‘star-in-crescent’ symbol associated with their goddess Ix Chel, lunar goddess of medicine. Ixchel was often depicted sitting in a crescent moon holding a rabbit. Since the Mayan word Lamat literally means “rabbit” and the Lamat glyph is also a symbol for Venus, decoded it becomes a depiction of the crescent moon ‘holding’ Venus. Thus this one Mandeville pot features three separate designs with Mayan Venus associations: the Lamat glyph, the quincunx glyph and the star-in-crescent design.

Coincidentally, during the same time period as the Mandeville site, a mound complex in the shape of a ‘star-in-crescent’ design was constructed at the Ortona Mounds site near Lake Okeechobee in Florida. Thus it was likely no accident the potters at Mandeville included this star-in-crescent design in their glyph. It was an idea spreading through Georgia and Florida at this same time period. There’s also evidence the Ortona Mounds site was also a Mayan-influenced site with its serpent mound, star-in-crescent mound complex, and extensive canals. The star-in-crescent mound complex was likely a temple to Ix Chel, one of the Poton Maya’s most important gods. The Poton Maya, also known as the Maritime Maya, were the seafarers of the Maya world and the most likely candidate to reach Florida and Georgia. Coincidentally, the Spanish noted three groups of “Maya” lived in Florida: the Mayaimi around Lake Okeechobee, the Mayajuaca near Cape Canaveral, and the Mayaca due east of the Crystal River site at Lake George. Between Lake George and the Crystal River site, the conquistador Hernando de Soto entered a province named Ocala. It consisted of two villages: Uqueten and Potano. Coincidentally, in Mexico, the Poton Maya lived in the province of Acala with their neighbors the Yokot’an.

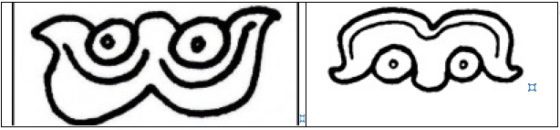

The Mandeville site also featured a pottery design similar to the Mayan Ek glyph which means “star.” Among the Maya, this w-shaped glyph was oriented both right-side up and upside down:

Here’s the version from the Mandeville site:

This multitude of Venus and star glyphs at the Mandeville site is consistent with research on Swift Creek pottery at other sites. This suggests there was a Venus cult at the Mandeville site and elsewhere. Among the Maya, Venus was associated with life, death and rebirth. Since these glyphs were found on pottery within Mandeville’s burial mound, they are in the proper context for such “rebirth” symbolism.

Finding one such similarity between a design in Georgia with a Mayan glyph could be dismissed as coincidence. Finding three such designs in Georgia that each matched a separate version of the three known Mayan Lamat glyph designs, the cross-shaped, diamond-shaped, and cross-and-diamond-shaped, decreases the probability that the similarities are due to chance.

Finding them on pottery within the right context, i.e., burial mounds, further decreases chance as an explanation. Finding them along with figurines that also have a strong Mayan appearance further decreases random chance as an explanation. Finding them at a location that also had the same architectural and town planning designs as the Maya further decreases chance as an explanation.

The odds of all of these similarities from architecture, town planning, symbols and figurines all happening at the same time at the same location and being due to chance is astronomical. The simplest explanation is that these similarities are the result of contact between tribes in Georgia and the Maya.

Archaeologists have long noted that the Mandeville site had trade connections with the Crystal River site in Florida. The Crystal River site has long been noted for its Mayan characteristics. Recent research shows Crystal River was the location of a Venus burial cult. Despite all the evidence of a connection between the Crystal River site and the Maya, researchers suggested in the book New Histories of Village Life at Crystal River, the Crystal River site borrowed the ideas from the Mandeville site instead:

“Mounds A, H, and K [at Crystal River] were probably not the earliest such features in the region; at a minimum, the platform mounds at Mandeville (in southwestern Georgia),…would seem to date slightly earlier. There is relatively good evidence of contact between Crystal River and Mandeville in the form of the sharing of rare negative-painted and incised ceramics…so we don’t dismiss the possibility that the idea of building platform mounds was borrowed from elsewhere. But it is probably safe to rule oft McMichael’s idea that Crystal River was a waypoint for Mesoamerican travelers…” (p.139)

Yet, as we now see, the Mandeville site has just as many Mesoamerican similarities as does the Crystal River site, thus shifting the source of influence to Mandeville doesn’t solve the problem of the ultimate origin of that influence.

The simplest explanation is that Poton Maya traders explored the coastal areas of the Southeastern U.S. around 1 AD and set up ports for the extraction and accumulation of natural resources to send to market back in Mexico. The megacities in Central Mexico (Teotihuacan, Cholula) and Southern Mexico (El Mirador, Tikal, Palenque, Copan) would create high demand for such resources. These raw materials would then be transformed or consumed and disappear amongst the tens of millions of other trade goods circulating throughout Mesoamerica.