A dog’s life long ago

BY GEORGE PAWLACZYK

News-Democrat

BROOKLYN – In ancient Illinois, small dogs were made to carry or pull

sacks of firewood until the tips of their vertebrae broke.

Sometimes their heads were lopped off with stone axes during sacrificial

ceremonies. Most often, they were buried with the trash.

No wonder canines kept by Indians in the Midwest were described in early

European explorers’ journals as nasty tempered and prone to bite. They

were also believed to be unable to bark but still served as watch dogs,

perhaps by nibbling on a sleeping Indian’s toes.

Nevertheless, an evolving archaeological record in the metro-east shows

that these small 25- to 35-pound primitive animals became as ingrained

in ancient human existence as today’s pampered canine pets.

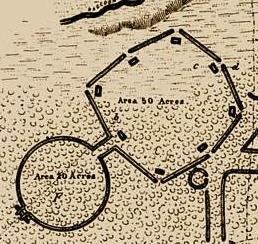

In Southern Illinois a thousand years ago, it was truly a dog’s life,

according to 60 complete or partial dog skeletons recovered from the

remarkably well-preserved, buried remains of a village from an era

archaeologists refer to as “Terminal Woodland.” The site is just outside

Brooklyn and is well clear of a nearby modern cemetery.

This fishing village was primarily occupied until about 950 A.D., or

just before the explosion of mound building that marked the more well-

known Mississippian Culture, whose members built the raised earthen

complex at the Cahokia Mounds Interpretive Center a few miles away.

The skeleton total from the Brooklyn site, first excavated in 2003, is

probably a North American record for the recovery of prehistoric dog

remains, said Joe Galloy, a Harvard-trained archaeologist. Galloy’s

specialties include interpreting the relationship between dogs and the

earliest Americans.

“If there is something that really pulls on the muscles, this bone, the

spinous process will fracture and reheal, and this is an example of

one,” said Galloy, holding up a delicate, deformed vertebra on which the

shark-fin like bone tip that anchors back muscles was bent.

“You see this in modern sled dogs,” he said, “This comes from being used

as pack animals, probably hauling firewood.”

On a large sheet of white paper spread on a table in front of Galloy at

the offices of the Illinois Transportation Archaeological Research

Program in Belleville, was the nearly complete skeleton of a young,

female dog recovered from the excavation site.

Galloy said this creature is descended from wolves that probably prowled

human camps and dumps 15,000 or so years ago in Europe and Asia and

gradually changed in appearance to resemble today’s dogs. Galloy said

the wolves, in return for scavenging, became the eyes and ears of the

humans and eventually became their hunting partners.

At another archeological site — the Koster Site along the Illinois

River in Calhoun County — one of the earliest North American dog

burials was uncovered in the 1970s. Radiocarbon dating showed it is

about 8,500 years old.

This animal, however, was probably a revered hunting dog and was

interred separate from a trash pit and had been reverently laid on its

side, just like rare human burials from this much earlier time.

But the dogs found by excavating teams at the Brooklyn dig headed by

Galloy and site supervisor Brad Koldehoff were not hunting partners. By

the time of this particular village, fishing and growing corn had

replaced nomadic hunting.

The Brooklyn site, which has gained a national reputation, is officially

known as “Janey B. Goode.” The nickname derives from the old Chuck Berry

song and is a tribute to the location’s archaeological riches.

“In contrast to earlier times, when the men went out hunting and the

dogs went with them and were very highly valued, at this time people

settled in one spot and the dogs became women’s’ helpers,” he said.

Another use, albeit a grisly one, was as sacrifices, probably to dispel

sickness in humans.

Six of the dogs, all males, were found buried and headless. Two dogs

were found with their heads still intact, but with their skeletons bound

back to back with the skulls facing east and west.

Dog remains found from a time a few hundred years later at Cahokia

Mounds were burned and had cut marks indicating the creatures had been

used as food, said Koldehoff, the excavation director. Koldehoff pointed

out that within a span of maybe 500 to 600 years, early dogs went from

hunting partners, to pack animals to dinner fare.

But weren’t there some ancient people, children perhaps, who cuddled

primitive puppies and maybe even played with them?

Koldehoff said he thinks that had to have happened, but there is no

physical proof.

“There’s certain things you can’t dig up,” he said. “You can’t dig up a

dance. You can’t dig up a song. And you can’t dig up somebody petting a

dog.”

Contact reporter George Pawlaczyk at gpawlaczyk@bnd.com and 239-2625.

© 2006 Belleville News-Democrat and wire service sources. All Rights

Reserved.

http://www.belleville.com