Evidence of Fireworks in Ancient America?

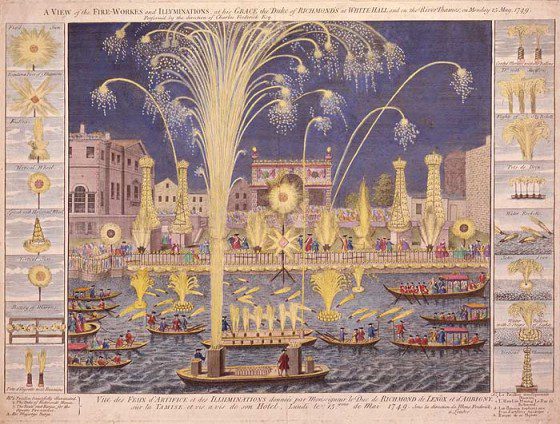

Eyewitness accounts of what appears to be fireworks were recorded by the earliest Spanish explorers of the South Carolina coast in the 1520s. These fireworks were used at the time of the chief’s death to trick the commoners into thinking the chief had supernatural abilities.

Eyewitness accounts of what appears to be fireworks were recorded by the earliest Spanish explorers of the South Carolina coast in the 1520s. These fireworks were used at the time of the chief’s death to trick the commoners into thinking the chief had supernatural abilities.

In 1526, Spanish explorer Lucas Vazquez de Ayllon landed in modern-day South Carolina around the area of the Santee River. He visited with many of the Native American tribes in the area and recorded their customs, rituals, and ways of living. While visiting a province named Duhare he witnessed many unusual things.

First, he noted that the people of this province were white not Native American. Second, he noted that the king of Duhare, named Datha, and his wife were much taller than the commoners and lived in a palace built of stone. He noted their hair was brown and hung to the ground. If tall, long-haired caucasian people living in a stone palace in South Carolina in 1526 isn’t unusual enough, the next observation certainly is. Ayllon noted that these people were in possession of some form of pyrotechnic devices including sparklers and rockets.

Ayllon’s accounts were recorded by Peter Martyr d’Anghiera in his book De Orbe Novo. The reference to sparklers and rockets appears as follows:

“Another fraud of the priests is as follows: When the chief is at death’s door and about to give up his soul they send away all witnesses, and then surrounding his bed they perform some secret jugglery which makes him appear to vomit sparks and ashes. It looks like sparks jumping from a bright fire, or those sulphured papers, which people throw into the air to amuse themselves. These sparks, rushing through the air and quickly disappearing, look like those shooting stars which people call leaping wild goats. The moment the dying man expires a cloud of those sparks shoots up 3 cubits high with a noise and quickly vanishes. They hail this flame as the dead man’s soul, bidding it a last farewell and accompanying its flight with their wailing, tears, and funereal cries, absolutely convinced that it has taken its flight to heaven. Lamenting and weeping they escort the body to the tomb.” Testimony of Francisco de Chicora, paragraph 12

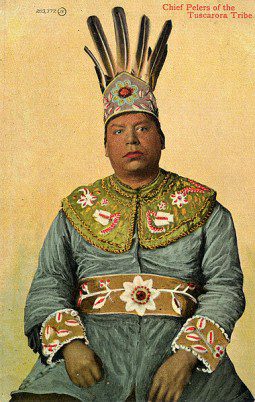

Two hundred years later in the early 1700s among the Tuscororas in nearby North Carolina another witness to such an event was Baron von Graffenreid. His description, recorded in The Colonial Records of North Carolina, is as follows:

“After the tomb was covered, I noticed something which passes imagination, and which I should not believe, had I not seen it with my own eyes. From the tomb arose a little flaming fire, like a big candle-light, which went up straight in the air, and noiselessly, went straight over the cabin of the deceased widow, and thence further across a big swamp above 1 mile broad, until it finally vanished from sight in the woods. At that sight, I have way to my surprise, and asked what it meant, but the Indians laughed at me, as if I ought to have known that this was no rarity among them. They refused, however, to tell me what it was. All that I could ascertain was that they thought a great deal of it, that this light is a favorable omen, which makes them think the deceased a happy soul, but they deem it a most unpropitious sign when a black smoke ascends from the tomb. This flying flame, yet, could not be artificial, on account of the great distance; it could be some physical phenomenon, like sulpurous vapors, but this great uniformity in its appearance surpasses nature (Saunders 1886-1890, I:982).” Colonial Records of North Carolina.

What is one to make of the use of pyrotechnic devices among the inhabitants of North and South Carolina between the years 1500-1700? And who was this village of white people known as the Duhare who were the first to be witnessed using these fireworks in their rituals?

Fireworks were first invented in China in the 7th century, were known in the Middle East by 1240 and the earliest evidence of rocket-propelled fireworks is from 1264. Yet, according to Wikipedia, fireworks didn’t become available in Europe until the 1650s. This is over 70 years after these pyrotechnic devices were first witnessed in South Carolina which likely explains why the Spanish in 1526 and the English in the early 1700s were so shocked and amazed by these displays. They had, in fact, never seen fireworks before. So who could have brought fireworks to the southeastern United States before these pyrotechnic devices had even arrived in Europe?

As stated earlier, the province of Duhare was the first place where such pyrotechnic devices were witnessed and recorded by the first European explorers. The Spanish claimed the Duhare were white people who had herds of deer which they milked for cheese production as well as flocks of chickens, ducks and geese. While ducks and geese are native to North America, chickens are not. Thus these mysterious white inhabitants of South Carolina had fireworks and chickens long before such things are believed to have arrived in the Americas.

The Spanish chroniclers wrote the following about the Duhare:

“Leaving the coast of Chicorana on one hand, the Spaniards landed in another country called Duhare. Ayllon says the natives are white men, and his testimony is confirmed by Francisco Chicorana. Their hair is brown and hangs to their heels. They are governed by a king of gigantic size, called Datha, whose wife is as large as himself. They have five children. In place of horses, the king is carried on the shoulders of strong young men, who run with him to the different places he wishes to visit.” Anghiera, Pietro Martire d’, 1457-1526; MacNutt, Francis Augustus, 1863-1927. De orbe novo, the eight Decades of Peter Martyr d’Anghera; (Kindle Locations 3670-3673). New York, London, G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Further details of the Duhare were provided elsewhere in these same accounts:

“In all these regions they visited, the Spaniards noticed herds of deer similar to our herds of cattle. These deer bring forth and nourish their young in the houses of the natives. During the daytime they wander freely through the woods in search of their food, and in the evening they come back to their little ones, who have been cared for, allowing themselves to be shut up in the courtyards and even to be milked, when they have suckled their fawns. The only milk the natives know is that of the does, from which they make cheese. They also keep a great variety of chickens, ducks, geese, and other similar fowls. They eat maize-bread, similar to that of the islanders, but they do not know the yucca root, from which cassabi, the food of the nobles, is made. The maize grains are very like our Genoese millet, and in size are as large as our peas. The natives cultivate another cereal called xathi. This is believed to be millet but it is not certain, for very few Castilians know millet, as it is nowhere grown in Castile. This country produces various kinds of potatoes, but of small varieties. Potatoes are edible roots, like our radishes, carrots, parsnips, and turnips. I have already given many particulars, in my first Decades, concerning these potatoes, yucca, and other foodstuffs.” Anghiera, Pietro Martire d’, 1457-1526; MacNutt, Francis Augustus, 1863-1927. De orbe novo, the eight Decades of Peter Martyr d’Anghera; (Kindle Locations 3679-3688). New York, London, G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Further on the account mentions they possessed a twelve-month calendar, metal and olive trees:

“Their year is divided into twelve moons. Justice is administered by magistrates, criminals and the guilty being severely punished, especially thieves. Their kings are of gigantic size, as we have already mentioned. All the provinces we have named pay them tributes and these tributes are paid in kind; for they are free from the pest of money, and trade is carried on by exchanging goods. They love games, especially tennis; they also like metal circles turned with movable rings, which they spin on a table, and they shoot arrows at a mark. They use torches and oil made from different fruits for illumination at night. They likewise have olive-trees.” Anghiera, Pietro Martire d’, 1457-1526; MacNutt, Francis Augustus, 1863-1927. De orbe novo, the eight Decades of Peter Martyr d’Anghera; (Kindle Locations 3774-3779). New York, London, G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

So who were these white people called the Duhare who raised chickens and possessed fireworks? One theory is that they were Irish. A researcher noted that the name Duhare could be the Gaelic word du h’Eire which he translated as “place of the Irish.” Actually, the dú prefix in Gaelic means “black/dark” and Eire means “Ireland” thus the proper translation would be “black Ireland.” Black Irish have been referred to throughout history and this description appears to refer to Irish with dark hair and eyes, just as the people described by Ayllon in Duhare. Interestingly enough, people referred to as “black Irish” have long been known in the Southeastern United States and were thought to be descendants of Spanish and Native Americans. The preceding evidence suggests this may not be the case since the Duhare were already in America at the time the Spanish arrived.

Additionally the Irish definitely had chickens and were known for milking deer as recorded in an Irish lullaby called “Bainne nam faith“:

On milk of deer I was reared.

On milk of deer I was nurtured.

On milk of deer beneath the ridge of storms

on crest of hill and mountain.

While this may explain the presence of white people in the southeastern United States in 1526 it does nothing to explain the presence of fireworks which weren’t known in Europe until the 1650s.

As noted previously, fireworks were invented in China and interestingly, researcher Gavin Menzies in his book 1421: The Year China Discovered America has argued that the fleets of Chinese Admiral Zheng He visited the Americas in 1421. If this fleet had reached South Carolina could they have given fireworks to the locals as gifts?

There are still many mysteries regarding ancient America which only further research will solve.

Pingback: The Testimony of Francisco de Chicora

Pingback: Evidence of Fireworks in Ancient America? | Mindscape Magazine | Scoop.it